top of page

PHOTOS

The Institutions

Fergus Falls State Hospital, circa 1928. The building, based on the Kirkbride plan, was the third hospital for the insane in Minnesota. It opened in 1890 and was completed in 1912. The building was more than one-third of a mile long and housed nearly two thousand patients by 1930. Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

The Institutions

Aerial view of Anoka State Hospital, 1937. The hospital opened in 1900 as an asylum for "hopeless cases." It was built on the cottage plan, a popular alternative to the Kirkbride model. Connected by underground tunnels, cottages were considered more homelike, and patients were grouped by behavior or condition. The term asylum was dropped in favor of hospital in 1937, though conditions did not change as a result. Photograph by Leo A. Moore, Sf. Paul Daily News. Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

The Institutions

Faribault State School for the Feeble-Minded, circa 1900. At that time, the school housed up to fifteen hundred intellectually disabled children and adults in overcrowded conditions. The building was razed in 1957. Photograph by Henry H. Altschwager. Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

The Institutions

Anoka State Hospital staff, July 1940. Front row, left of center, Dr, Walter P. Gardner, superintendent. Front row, second from far left, Esther Nelson, supervisor of nurses. Attendants were not pictured among the professional staff in this photograph. Courtesy of the Anoka County Historical Society.

The Institutions

Minnesota mental hospital leaders, circa 1949-50. From left: Dr. Royal Unit of the State Division of Public Institutions (DPl); Gray, Mental Health Carl Jackson, head of DPI; and Dr. Magnus C. Petersen, superintendent of Rochester State Hospital. Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

The Conditions

One hundred men slept in overcrowded attic rooms like this one, unventilated and poorly insulated. Lacking dressers or closets, they stored their clothes on the floor. In some hospitals, beds were so close together that the patient could not climb out on either side but had to crawl over the foot. Photograph by Arthur Hager, Minneapolis Tribune. Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

The Conditions

Women patients in straitjackets, euphemistically called camisoles, were tied to wooden benches with leather straps, bound at their ankles, and left unattended for hours at a time. Photograph by Arthur Hager, Minneapolis Tribune. Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

The Conditions

A typical institution meal was a watery pork stew, potatoes, string beans, and milk. Milk was served in tin bowls, and the only utensil provided to patients was a tablespoon. Photograph by Arthur Hager, Minneapolis Tribune. Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

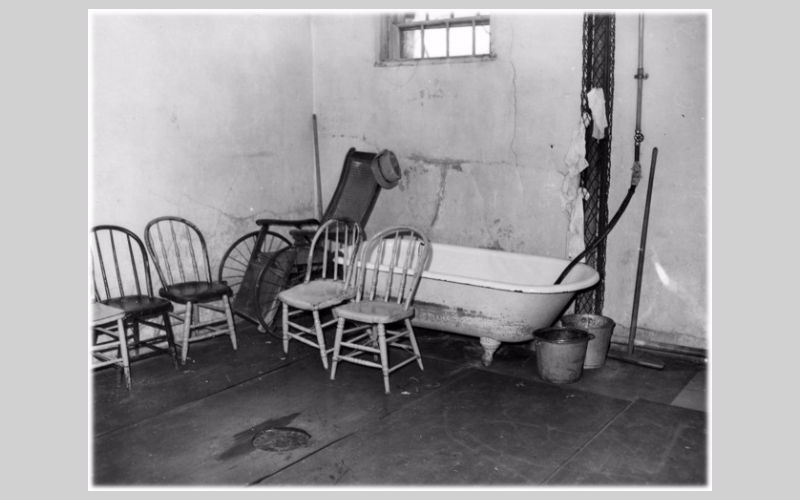

The Conditions

The dilapidated shower rooms at Rochester State Hospital also served as storage closets for mops, brooms, and chairs. Showers had no towels or soap unless supplied by the attendant, and the patients’ clothing was tied in a bundle and handed back as they exited. Courtesy of the History Center of Olmsted County.

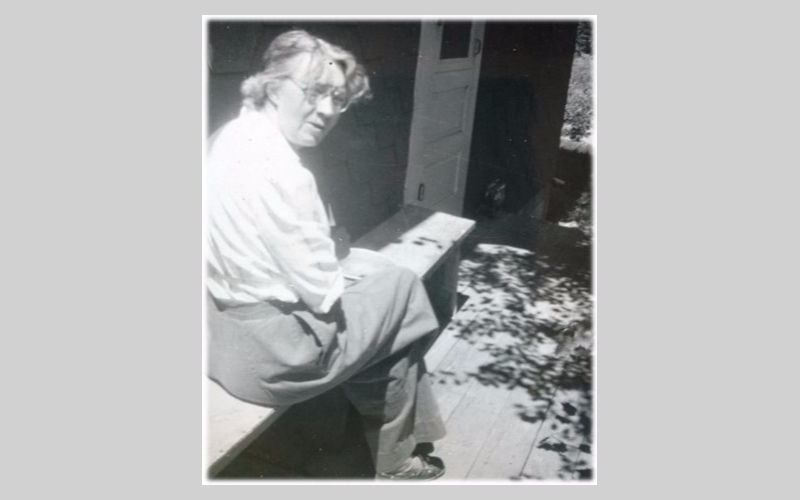

The Crusaders

Engle Schey, the intrepid, dedicated fighter for mental hospital reform. 1940s. Courtesy of Roxanne Butzer.

The Crusaders

Spruce Valley homestead, 1897. From left, Henrik (“Fasteman”) and Olina (“Faste”), two-year-old Engla (in stripes), Anders, and Helene, holding baby Josie. The name Faste was colloquial for “father’s sister.” Anders was raised by his aunt Olina and uncle Henrik in Norway. Engla wrote that he brought them to America to “live out their days with us.” Courtesy of Ruth and John Schey.

The Crusaders

Schey family portrait, taken in Thief River Falls, circa 1913. From left, mother, Helene (seated), Josie, Helen, Ole, Engla, and father, Anders. Courtesy of Ruth and John Schey.

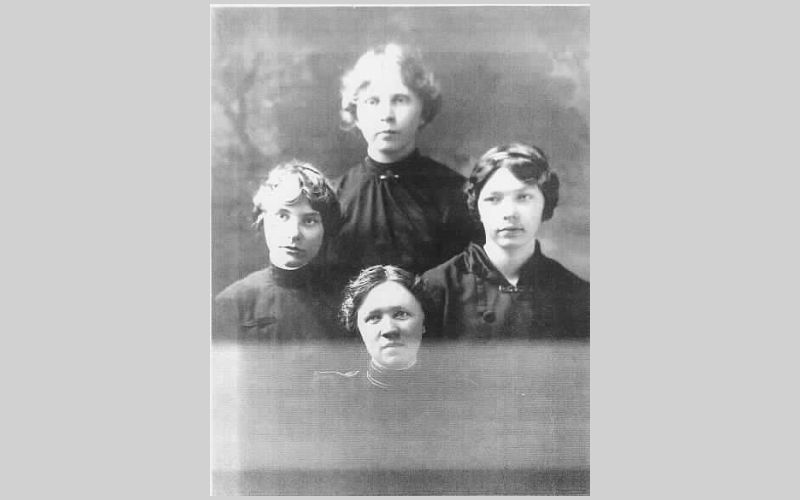

The Crusaders

The Schey cousins, 1920s. Clockwise from bottom: Engla, in her Salvation Army uniform, cousins Jennie and Emma, and sister Josie. Jennie and Emma were Engla’s lifelong friends. Courtesy of Roxanne Butzer.

The Crusaders

Reverend Arthur Foote, circa 1945. Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

The Crusaders

Genevieve Steefel, active in social work, civil rights, and fair housing, was secretary and later vice-chair of the MUC Committee on Mental Hospitals, 1940s. Courtesy of Sarah Steefel.

The Movement

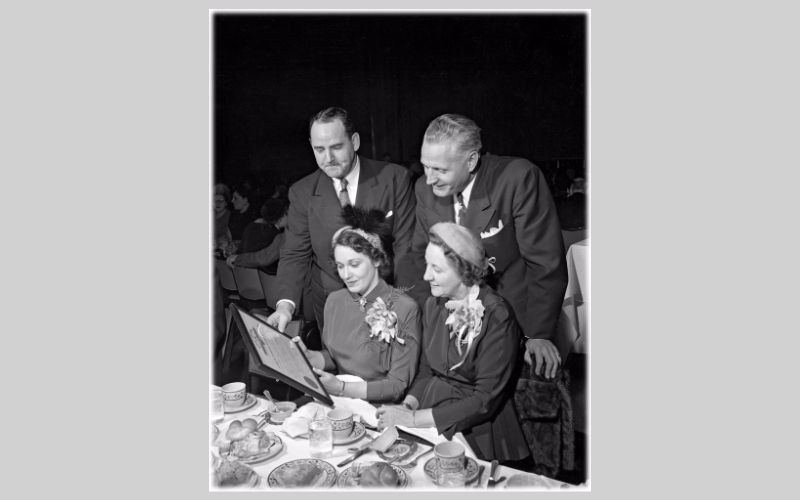

From left, Minnesota Governor Orville Freeman (1955-61) meets with journalist and Unitarian reformer Ed Crane, Minneapolis Tribune reporter Geri Hoffner, and Arthur Foote, circa 1954. Author's collection.

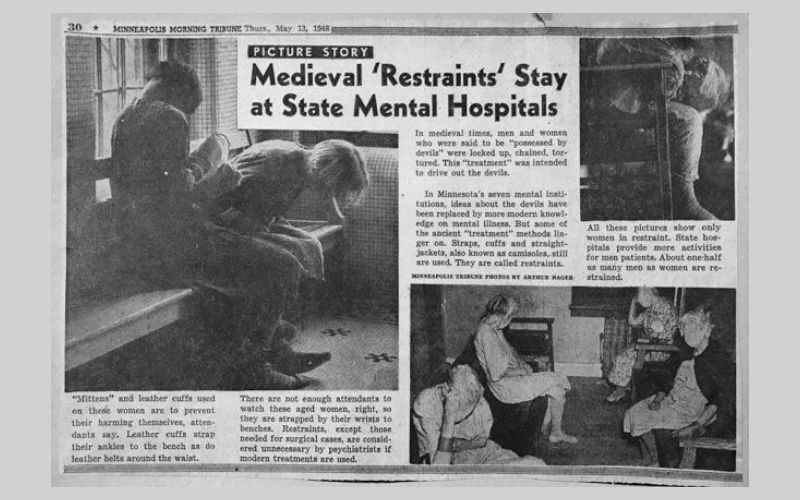

The Movement

The May 13, 1948, installment of the eleven-part Minneapolis Tribune discussion of conditions in Minnesota’s mental hospitals. As part of the series, reporter Geri Hoffner and photographer Arthur Hager visited all seven hospitals. This blockbuster series galvanized public opinion toward reform. Author’s collection.

The Movement

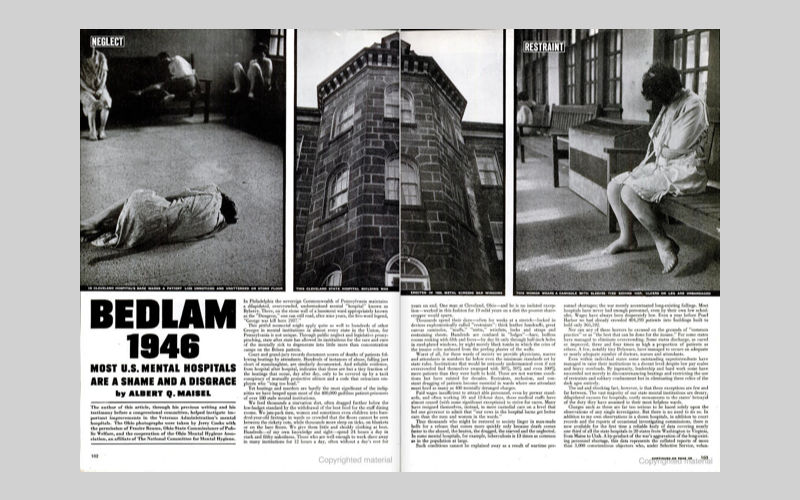

On May 6, Life, the popular and widely circulated magazine, published “Bedlam 1946: Most U.S. Mental Hospitals Are a Shame and Disgrace” by Albert Q. Maisel.

The Movement

In 1949, Dr. Donald Hastings (far left), head of the University of Minnesota’s Psychiatry Department, shows Govenor Youngdahl and State Senator Gerald Mullin (center) one of the occupational therapy treatments at University Hospitals. Mullin, a North Minneapolis Democrat, was a strong supporter of the university and the mental health reform effort. Photograph by the Minneapolis Star. Courtesy of the Hennepin County Library Special Collections.

The Reforms

Governor Youngdahl took his case for mental health reform directly to a joint session of the state legislature in 1949. Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

The Reforms

In 1950 Dr. Ralph Rossen was officially appointed commissioner of mental health for the state of Minnesota. Looking over the certificate are Dr. Rossen (left), Governor Youngdahl. Photograph by the St. Paul Dispatch/Pioneer Press. Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

The Reforms

Staff and patients watch as Governor Luther Youngdahl burns straitjackets, leather straps, and other devices used to restrain patients at Anoka State Hospital, October 31, 1949. Photograph by the St. Paul Dispatch/Pioneer Press. Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

The Reforms

As part of their reform effort, the Minnesota Unitarians organized a summer work program for young people to volunteer at Hastings State Hospital under the auspices of the Unitarian Service Committee. In this photograph, a volunteer feeds an elderly bedridden patient. Author’s collection.

The Reforms

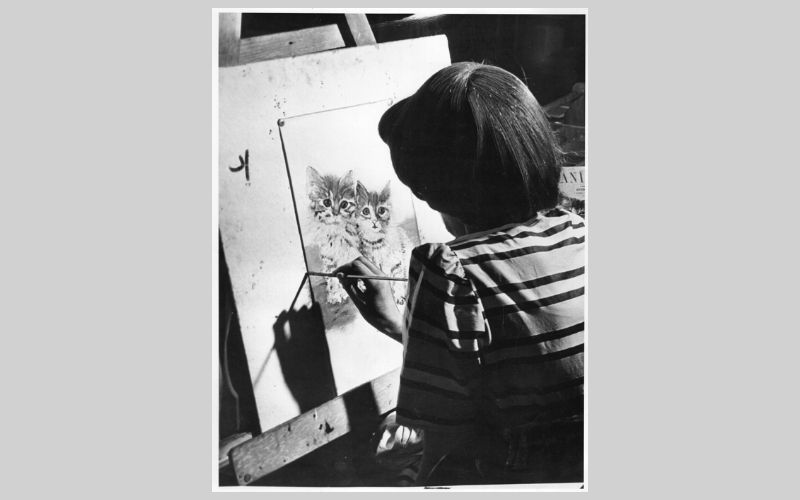

Occupational and recreational therapy, in the form of parties, dances, crafts, and sports, were a hallmark of the reformed mental health program. The patient pictured here showed her work in an impressive hospital art exhibit. Photograph by Arthur Hager, Minneapolis Tribune. Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

The Reforms

New library building at Hastings State Hospital, 1950s. Funds allocated during the reforms financed the construction of new buildings and renovation of older ones. Engla Schey organized the newsletter written and produced by patients that met in the library space. Copyright University of Minnesota, College of Design.

bottom of page